This article was originally published in Politico on March 20, 2016.

Tel Aviv — This might be the most surprising poll from a wild, unpredictable 2016 campaign: One in four Israeli Jews would vote for Donald Trump.

The real estate mogul does not have a coherent position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, except to break with decades of Republican orthodoxy and announce that he would be “neutral.” His GOP rivals repeated that line endlessly, hoping it would blunt Trump’s rise in the polls. It didn’t.

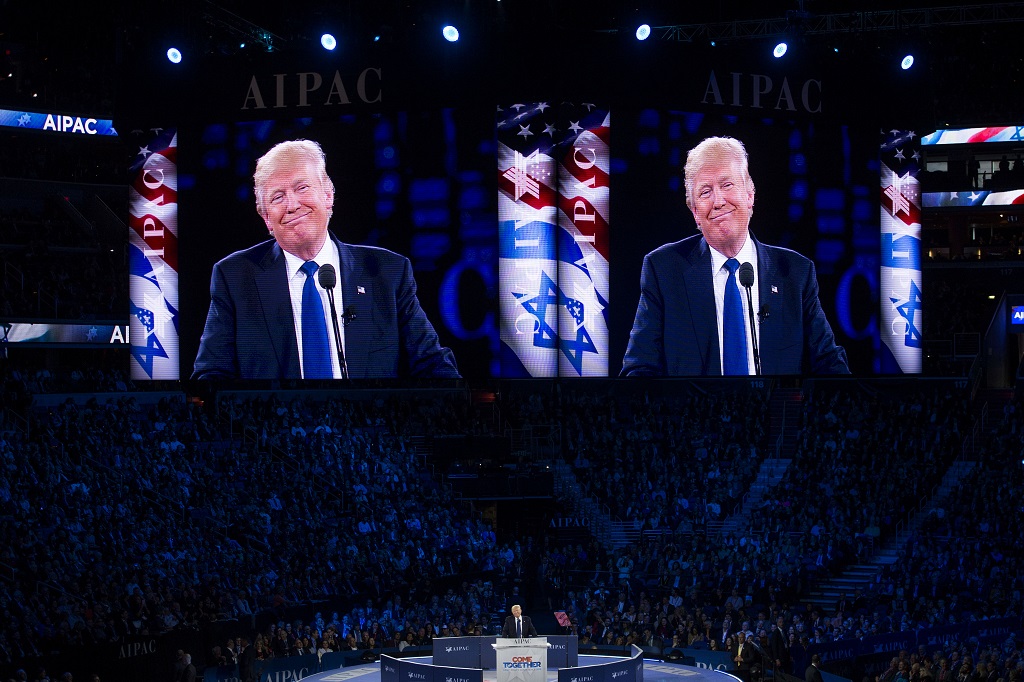

His campaign, run in the style of an authoritarian strongman, has earned him sharp criticism from American Jews, the largest Jewish community outside of Israel. And his backers include a former leader of the Ku Klux Klan who hopes Trump will “rehabilitate” Hitler’s image, a statement that ought to give pause to anyone in Israel. Indeed, the big question looming over this week’s American Israel Public Affairs Committee convention is just how many delegates will walk out during Trump’s speech.

Yet, a recent poll found Trump was by far Israel’s favorite GOP candidate, and the second-most popular overall. A plurality even thought he would be best at “representing Israel’s interests,” better than Hillary Clinton, with her decades of advocacy at the highest levels of government.

Those numbers could rise further still, after a spate of positive coverage in Israel’s most widely read newspaper, Israel HaYom, owned by billionaire casino magnate Sheldon Adelson. After months of scant coverage, the shift is a sign that Adelson—a major force in both Israeli and American politics—is reluctantly embracing Trump.

All of this presents a major dilemma for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has worked for years to align Israel with the GOP. The party’s presumptive nominee is now being spurned by the same establishment figures, men like Sens. John McCain and Lindsey Graham, who make up Netanyahu’s “base” in Washington. Trump has no emotional attachment to Israel. And his success has upended the long-held belief that Republican voters care deeply about a candidate’s position on Israel.

In the United States, Trump has scrambled the political map, shattering the decades-old alliance between social conservatives and the Republican economic elite. In Israel, the confusion could become even more acute. Trump has already violated some of the tenets of the “special relationship.” And while his tough-guy persona and hostility toward Muslims have earned him surprising support from Israeli conservatives, his ascent is also a source of unease for policymakers: It creates a schism between an Israel that needs to work with Trump, and American Jews who despise him—and it could end up undermining the marriage between the GOP’s pro-Israel foreign policy elite and the broader Republican electorate.

“If I were advising Netanyahu, or indeed if I were Netanyahu himself, I would shut up for a few months.”

“The government is in a bind,” says Alon Pinkas, a former Israeli diplomat and adviser to Prime Minister Ehud Barak. “Trump in this respect is so unpredictable. If I were advising Netanyahu, or indeed if I were Netanyahu himself, I would shut up for a few months."

As with most of his policy positions, Trump’s views on Israel are a bit of a mystery. The “positions” page on his website doesn’t mention the Middle East. And his choice of foreign policy advisers offers little insight, because he has named only one: Donald Trump.

When he does talk about Israel, he offers platitudes and snippets of biography, like his daughter Ivanka’s conversion to Judaism. The candidate has made much of his role as the grand marshal of the 2004 Salute to Israel Parade, an entirely symbolic act. (Other previous marshals include the president of a circuit board company and a 13-year-old girl.)

The closest he came to a policy statement was on February 17, when Trump said he would be “sort of a neutral guy” when it came to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “A lot of people have gone down in flames trying to make that deal. So I don’t want to say whose fault is it,” he said at a town hall in Charleston. He doubled down the following week at a CNN debate in Texas: “It doesn’t help if I start saying I’m very pro-Israel,” he told Wolf Blitzer.

His chief opponents, on the other hand, both Republican and Democratic, have long records of supporting Israel. Ted Cruz promised to “rip to shreds this catastrophic Iranian nuclear deal” on his first day in office. Both he and Marco Rubio vowed to move the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, long a demand of the Israeli right.

Clinton, of course, has publicly backed Israel for decades, as first lady, senator and secretary of state. She now retroactively criticizes the Obama administration’s 2009 push for a settlement freeze, a policy she promoted at the State Department, and promised to invite Netanyahu to the White House “in my first month in office.”

It was no surprise that Clinton won the largest share of the Israeli vote, 38 percent, in a poll conducted earlier this month by Walla, the country’s most popular online portal.

But Trump placed a surprising second, with 23 percent, and 26 percent among Israeli Jews. Rubio, for all the positive coverage he got in the conservative daily Israel HaYom and elsewhere, scored just 4 percent. More striking, when asked which candidate would best represent Israel’s interests, a plurality picked Trump: He edged out Clinton, 25-24.

He finds his support largely on the Israeli right. “After a Barack, you always need a strong man,” quips one Tel Aviv restaurant owner and Likud voter (a play on words: Ehud Barak’s short-lived premiership ended with a landslide 2001 defeat to Ariel Sharon). Conservatives dismiss Cruz as too strange and Christian, and Rubio as too much like Isaac Herzog, the baby-faced Labor chief who failed to unseat Netanyahu last year.

The thrice-married mogul who once owned the Miss USA pageant has even received favorable coverage in the ultra-Orthodox media; one profile noted his Jewish business associates, and the fact that his daughter keeps kosher and observes the Sabbath.

His negative comments about Muslims don’t hurt him in Israel, either. “The Israeli public is getting everything through the Israeli media in Hebrew, so it’s not like they see everything,” says Tal Schneider, an Israeli political analyst. “They don’t grasp the entire candidate, they just see his anti-Muslim sentiment, and then they say to themselves, ‘ah, obviously we know that, because we live with the Muslims here.’”

Dr. Camil Fuchs, a well-known pollster who worked on the survey, says party affiliation also played a role in the findings. “Clinton is viewed as cooler to the Israel issue” because she’s a Democrat, he says. “Anything Republican is seen as better for Israel.

This is certainly Netanyahu’s view, though he professes neutrality in U.S. politics: Israel’s long-serving prime minister has yoked his Likud party, and his country, to the Republicans. He welcomed Mitt Romney to Jerusalem during the 2012 campaign; his ambassador in D.C., Ron Dermer, worked on Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America; and of course there was last year’s infamous Iran speech, coordinated with Congressional Republicans instead of the White House.

A Gallup poll released last month found Americans from both parties were still overwhelmingly more sympathetic to Israel than the Palestinians. On questions of policy, though—rather than emotion—there are some signs of a split. A December poll from Brookings found a clear partisan divide: 76 percent of Republicans said a candidate’s position on Israel was deeply important to them, compared to 49 percent of Democrats; nearly half of Democrats, but only a quarter of Republicans, thought Israel had too much influence on U.S. policy. Asked how the United States ought to respond to continued settlement construction in the occupied West Bank, 49 percent of Democrats chose sanctions, versus 26 percent of Republicans.

It’s a clear choice, Netanyahu’s allies argue: The Republican Party, with its mix of evangelicals and national security hawks, is far more receptive to a right-wing Israeli government.

Except Netanyahu didn’t anticipate Donald Trump and his brand of nationalist isolationism. 73 percent of Republican voters in Florida last week cited domestic concerns—the economy, government spending and immigration—as their most important issue. Surveys from other states found similar numbers. The polls, admittedly, did not ask about foreign policy. But the primary results, coupled with Trump’s ambiguous position on Israel, suggest that Israel simply isn’t animating many voters.

And he probably didn’t anticipate that the GOP would ever nominate a candidate so anathema to American Jews. The umbrella organization for Reform Jewry, the largest community in the United States, accused him of “sowing seeds of hatred and division in our body politic.” Jewish commentators from across the political spectrum describe his rallies as “Nuremberg-esque” and accuse him of inciting violence. His views on Israel are barely a tertiary concern; the criticism is about how Trump’s campaign undermines social and political norms.

One wonders how a President Trump freed from the constraints of Republican ideology would deal with Netanyahu. Because if Trump has been consistent about one thing throughout a nasty, brutish campaign, it’s the joy he finds in humiliating his political foes. He joked that Mitt Romney would have “dropped to his knees” for a 2012 endorsement; he mocks a now-subservient Chris Christie at every turn. It’s not hard to picture him clashing with an Israeli government that called Secretary of State John Kerry “obsessive and messianic” and tried to undermine Obama’s signature foreign policy initiative. Vice President Joe Biden was humiliated on a 2010 visit when Israel announced a major settlement expansion just hours before his plane landed.

“Obama just shrugged it off, he’s cool, he’s ‘no-drama Obama,’” Pinkas says. “If Netanyahu says something critical, or anyone in his government says something, Trump is going to go berserk.”

Trump did endorse Netanyahu before the 2013 election, calling him a “winner,” the highest praise in the mogul’s vocabulary. But Trump’s candidacy appears to have cooled their relationship. Trump announced with much fanfare in December that he would visit Israel after Christmas. Netanyahu, who has mostly kept silent on the election, quickly distanced himself from the candidate, denouncing Trump’s call to ban Muslims from entering the United States. Trump took the hint and cancelled his visit; Israelis suspect he harbors a grudge.

One Israeli journalist who covers Netanyahu half-jokingly imagines the dialogue at the first Trump-Netanyahu meeting: “Listen, you Jew, your slick ways aren’t going to work with this White House,” Trump might warn. “Stop those f**king settlements now.”

It was hard not to feel a tinge of pity for Rubio as his once-anointedcampaign suffered one humiliation after another: the debate meltdown in New Hampshire, the crushing defeat in his home state.

“If Netanyahu says something critical, or anyone in his government says something, Trump is going to go berserk.”

For an observer in Israel, the saddest blow came on Thursday, on the front page of the country’s largest newspaper.

Israel HaYom is a free daily underwritten by Sheldon Adelson, the American casino magnate and GOP mega-donor. It serves primarily as Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s mouthpiece, a propaganda outfit thrust into your hands in shopping malls and rush-hour traffic. Two of his own cabinet ministers have likened it to Pravda, the official organ of the Soviet Communist Party.

But it also reflects the political preferences of its owner—and for the past year, the junior senator from Florida was clearly one of them. In April, when Rubio announced his candidacy, Israel HaYom fawned over the “spectacular show” he put on in Miami. Boaz Bismuth, the foreign editor, called Rubio “the most pro-Israel candidate that America has to offer.”

He turned out to be one of the least electable, too, and as the final polls showed that Rubio’s Florida-or-bust strategy would indeed bust, Israel HaYom changed its tune. Sunday’s front cover was a sympathetic account of Trump’s aborted Chicago rally. On Monday the paper led with an interview with Rudy Giuliani: “Trump isn’t afraid to say ‘Islamic terror,’” he said, calling the real-estate mogul “wise.”

“The minute you see Israel HaYom turning a page and starting to be more positive, it’s like the start of a storm,” Schneider, the political analyst, says. “Suddenly you see all of the commentators, all of the talking heads, the chitchat class, they just suddenly change.”

The denouement came on Thursday, the first issue published after Trump’s big win in Florida. “I love Israel,” the candidate declared atop a two-page spread, proclaiming his victory “tremendous news” for the state of Israel. The front cover carried a photo of Trump giving a thumbs-up—standing next to a grinning Bismuth. Rubio wasn’t even mentioned, like a disgraced party apparatchik airbrushed from the pages of Pravda.

The chattering classes in Israel saw a tactical shift—“a sign that Adelson finished the stages of grieving for Rubio,” one journalist joked. Netanyahu might soon have little choice but to meet with Trump, so the mogul needs a new image amongst the Israeli public. Several observers pointed to the Chicago rally as a turning point: It offered a compelling narrative, a tough right-wing leader besieged by angry liberals, that would resonate with Israelis who resent their own left.

Adelson himself was asked at a private event last month if he could support Trump. “Why not?” was his laconic response, in remarks first reported by Schneider. “Trump is a businessman. I’m a businessman. He employs many people."

AIPAC will offer Trump one of his largest platforms yet, a chance to look presidential. One imagines he will seize the opportunity, continuing a pivot to the general election that he started earlier this month, positioning himself a great unifier. (Or maybe not: he did tell the Republican Jewish Coalition that they probably wouldn’t support him because he refused to take their money.)

Many attendees at the conference have already made up their minds. A senior writer at Tablet urged delegates to walk out en masse during Trump’s speech. “AIPAC cannot be seen as legitimizing Trump, even if it provides him with a pulpit,” said Michael Koplow, the director of the Israel Policy Forum. Several groups of Jewish leaders are planning to boycott the event.

Trump could lose the nomination in a convention fight, or fall short in the general. But either way, his ascent poses an existential question: How should the Jewish state deal with a president who is anathema to most diaspora Jews?

Trump has already signaled that he’d try to broker a peace deal if he were elected president. “A [peace] deal would be in Israel’s interests,” Trump told ABC on Sunday, previewing Monday’s AIPAC speech. “I don’t know one Jewish person that doesn’t want to have a deal.”

Israel wants to be able to work constructively with the next president, whoever he may be. American Jews want to stop a bigoted candidate whose supporters, emboldened by his nativist rhetoric, yell things like “go to Auschwitz.” Perhaps never before have their interests diverged more sharply.